O. C. Peterson - U. S. Army Air Forces 1940-60

O. C. Peterson - U. S. Army Air Corps/ Air Force 1940-60

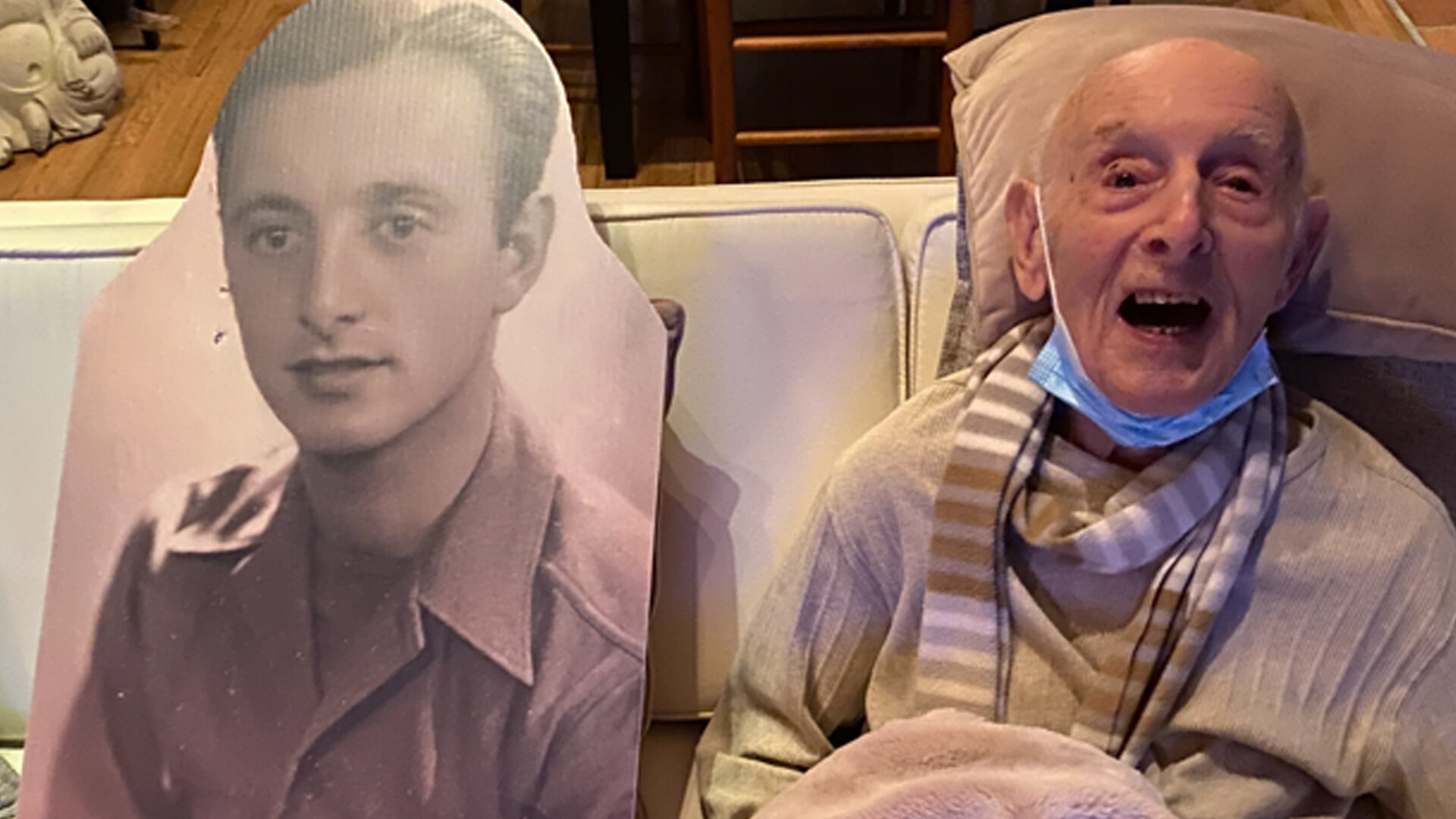

O. C. Peterson, Pete to his friends, was born in December 1918 and joined the Army Air Corps in 1940. He served as a navigator in the Army Transport Command during WW II flying supplies, ammo and cargo from the U.S. to Europe, China and Africa. He even delivered gold to the Flying Tigers for their payroll. After the war, he stayed in the reserves and was called back to active service to take part in the Berlin Airlift. Pete spent 12 years in the Army Air Forces and retired as a Lieutenant Colonel.

Pete died in 2019 at the age of 100.

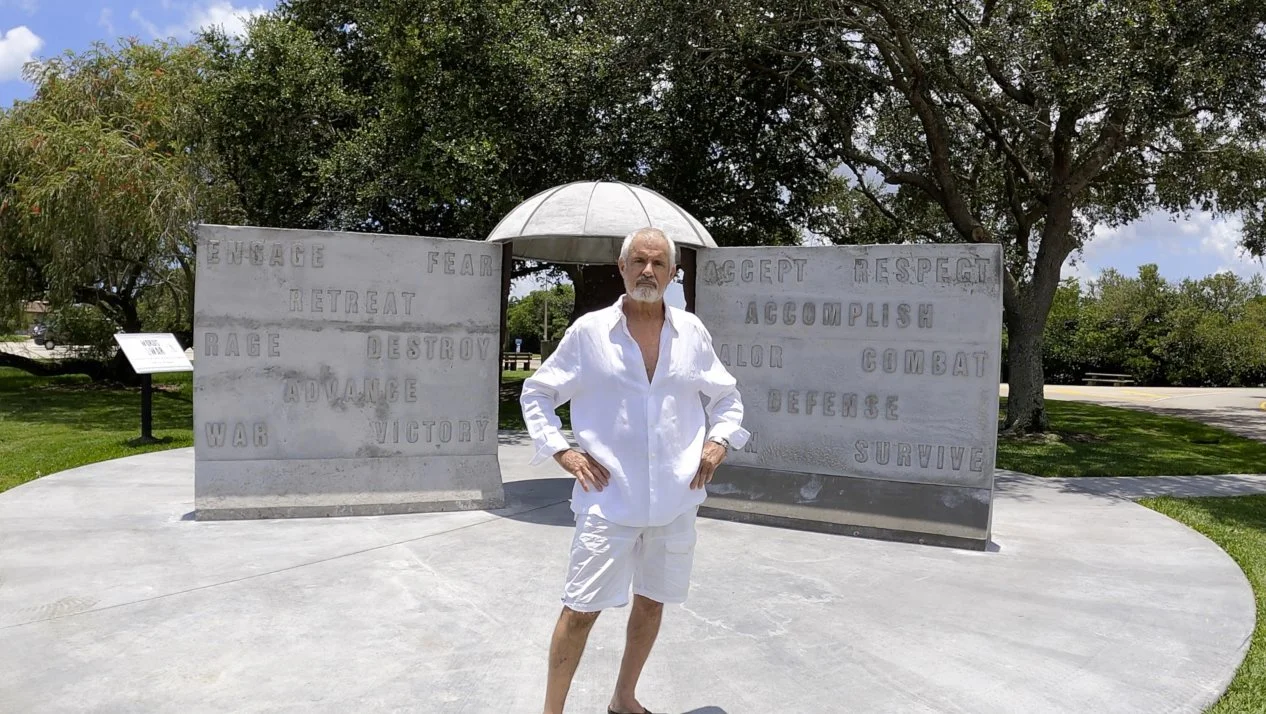

This video was produced by The Rowlinson Media Group, VERO BEACH, FL.

O. C. “Pete” Peterson 1918-2019

O. C. “Pete” Peterson, a long-time resident of Fort Pierce, and friend to many, died Saturday, October 26, 2019, at the age of 100. He was born on December 1, 1918, in Withee, Wisconsin, to Osmond A. Peterson, and Martha Fechner Peterson. His father was so skilled as a mechanic and craftsman that the family always had an income during the depression. There was an older sister, Marion, and a younger sister Carroll when the family moved to Wisconsin Rapids. O. C. graduated from high school in Wisconsin Rapids, lettering all four years in hockey. By working odd jobs he completed 3 semesters of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Wisconsin before running out of money in the summer of 1940. He joined the Army Air Corps in September of 1940, more than a year before Pearl Harbor, attending basic training in East St. Louis. Afterwards he was transferred to Chanute Field, Illinois, to train as an aircraft mechanic.

Throughout 1941 he was assigned to the 20th Pursuit Group, serving as a crew chief on a Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk. After Pearl Harbor he joined the first wartime Cadet Class and graduated as a 2nd Lieutenant, later graduating from Celestial Navigation School. With this training he could find his position anywhere upon the earth with a US Government issued A-10 Octant (similar to a sextant, but with an artificial horizon), a chronometer, and a set of sun and star tables. Polaris, Aldebaran, Bellatrix, and several dozen other selected stars, became his guides in the night sky, and he was selected to put his skill to use with the Air Transport Command. The ATC was charged with the delivery of aircraft, personnel, and cargo, to every theater of the war. In St. Joe, Missouri, while crew training in Mitchell B-25 medium bombers, he met a young but experienced transport pilot from Pan Am Airways, Lt. David B. Putnam, who was to become his best friend throughout the war years and for many years afterward. There at St. Joe, Lt. Putnam chose Pete to be his crew’s navigator, and at the end of training, they found themselves on a train bound for the 36th street airport in Miami.

In the service he was called “Pete” by the other airmen. His first training crew, after several flights across the Atlantic to destinations as far away as Karachi, eventually was broken up to provide qualified aviators to other newly forming crews. In all he flew across the Atlantic 96 times, to destinations in Africa, Europe, and Asia, with Chabua, India as one of the frequent terminal points. That was where the Hump crews would take aircraft and cargo into China. Another common destination was Baghdad, where the ATC crews would turn over A-20s to the Russians. In 1943, before Rommel was driven from Africa, the ATC crews used the “Fireball” route. On this flight plan crews would leave from Miami’s 36th street airport for Trinidad, then Belem, and stop at Natal, on the east coast of Brazil. When ready, they would make the Atlantic crossing, first to Ascension Island, a two-mile wide “aircraft carrier” of sorts, in the middle of the south Atlantic. It was an 8-hour flight to that tiny Island, followed by another similar flight to the coast of Africa at Dakar, Lagos, or Liberia. From there the flight would be to Khartoum, or Cairo, avoiding the coast of north Africa. Finally, later in the war, with the Germans pushed across the Mediterranean, the typical flight was in a C-54, delivering cargo to North Africa via the Azores on the ATC’s “Crescent Caravan” route, or Northern Europe via Newfoundland and Iceland on the “Snowball” route.

He navigated flights of 4 or 5 A-20s in formation, remembering them from his vantage point in the nose of the lead plane as “like flights of gracefully soaring pelicans.” His crew also delivered B-17s, B-24s, B-25s, B-26s, and B-34s or carried freight such as ammo or equipment in C-46s, C-47s, and C-54s. In all he navigated in over 20 aircraft types ranging from the two-engine B-34, to the 4-engine C-54. After World War II, at the invitation of his good friend Dave Putnam, he came to Fort Pierce for a two-week vacation and decided to stay. In 1947 he married Fort Pierce local Olive Dame Forkner, daughter of Judge and Mrs. Flem C. Dame, and began building custom homes. His new business was interrupted when he was recalled to active duty during the Korean War.

The family moved to Mobile’s Brookley Field in early 1951 and Pete resumed his role as celestial navigator on the old ATC “Crescent Caravan” and “Snowball” routes. He never flew the Pacific but resumed the Atlantic routes in place of the active duty MATS navigators who were being reassigned due to their extensive Pacific experience in WW II. The flight lines at Brookley were filled with C-54s, C-74s, C-119s, and C-124s, and he made flights in all these types. One of his assignments was the continued air supply to Berlin, even after the official end of the Berlin Air Lift. Another memorable flight was in a C-124, when the crew set a duration record of 17 hours, 40 minutes, while engaged in search and rescue in the North Atlantic. In early 1952 the family headed for a new assignment at Mountain Home AFB near Boise, Idaho.

They set up housekeeping in Boise, less than an hour’s drive northwest of the base, and got used to the thunder of B-29s passing overhead. The outfit Pete joined was called the Air Resupply and Communications Service, commanded by medal of honor winner “Killer” Kane, of Ploesti fame. The flights he navigated were unlike anything he had done before. As an example, Crew 6, with pilot Art Fields, might take their B-29 on a non-stop flight to a point near Phoenix, turn toward Las Vegas, and then make another turn northward to make a bee-line back to Mountain Home. The training was for the purpose of low-level insertion of personnel and equipment behind enemy lines. It must have seemed like a good idea at the time, but fortunately the unit was never deployed overseas. Their B-29s were war weary from the Pacific bombing campaign and had been stored in the desert for 5 years. Wiring harnesses and seals were badly deteriorated. Engine fires were not uncommon. On one mission, Crew 6 diverted to Ogden twice with engine fires. On another flight a bomb bay fuel tank valve broke and high-octane fumes filled the cabin. In early 1953, after taxiing to their parking spot, Crew 6 was met on the ramp by the operation officer explaining that the unit was being disbanded, and anyone that wanted out could go home. To a man Crew 6 left the service. The training flights had been very risky affairs, and now that the Korean War was winding down, each thought returning to civilian life was a great idea.

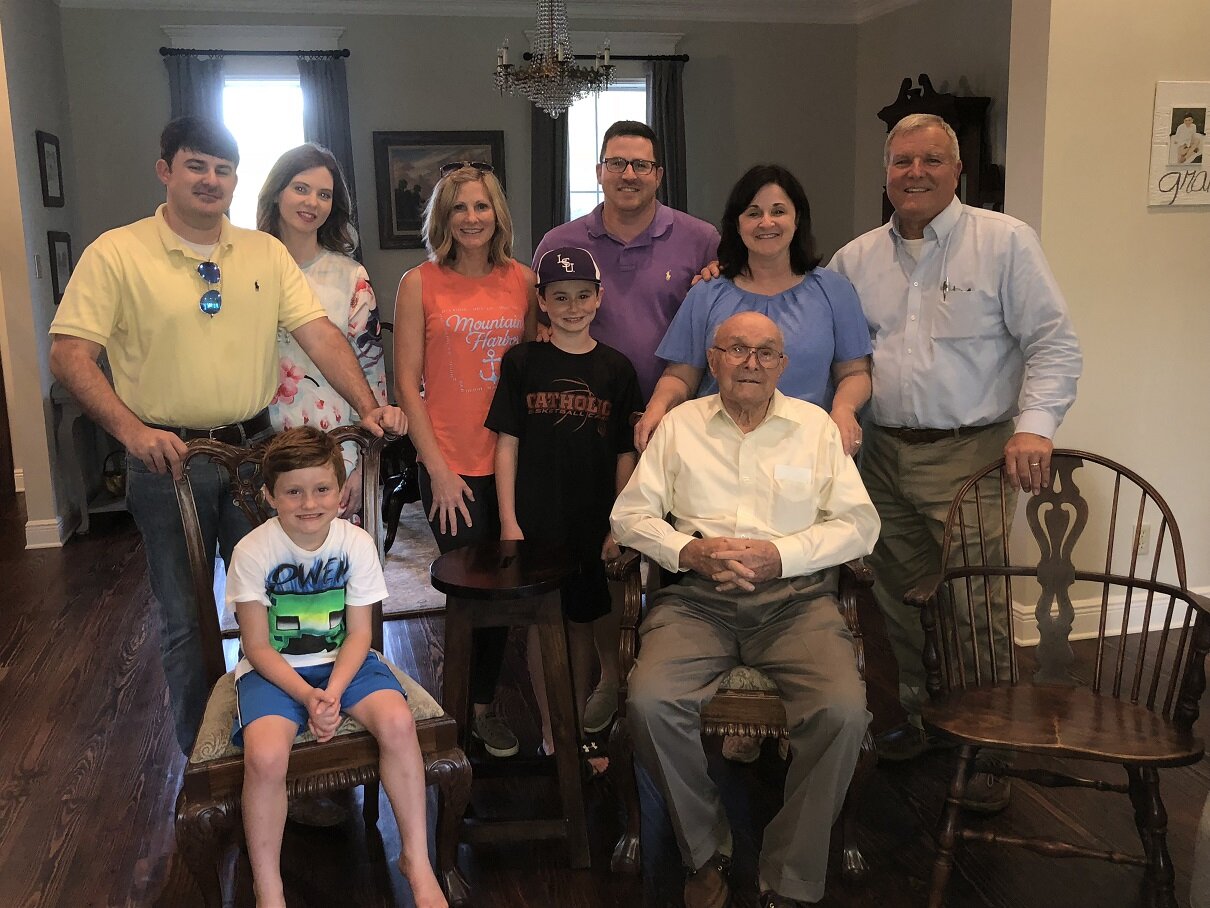

The family packed up and headed for Prairie du Sac, Wisconsin, where Pete’s mother and father had moved during WW II. “O. A.” had worked at the Badger Ordinance Works near Baraboo, Wisconsin, until the end of the war, and then had started a millworks shop. Now “O. A.” was suffering a temporary disability and Pete offered to help run the millworks shop while his father recovered. It was a much different place than Florida, Mobile, or even Boise, and the family enjoyed almost a year in Wisconsin before they set their sights again on Fort Pierce, Florida, arriving on New Year’s Eve, 1953. After over 3 years of Mayflower moving vans, multiple schools for the oldest son, and many miles accumulated on the 1950 Studebaker sedan, the family settled into a place called home. Pete resumed home construction and established a very successful building business that spanned the years 1954 to 2008. He remained in the US Air Force Reserve and retired after 20 years of service. During his long career as a builder in Fort Pierce he built hundreds of superb homes that attest to his skill and honest workmanship, including the oak-shaded colonial house he made for his wife and family on Delaware Avenue in the 1950s. After he retired he spent much of his time building his last house, a striking, original Florida “dream” house on a hidden lot in the subdivision he and Olive established just behind the Delaware house. Sadly, Olive died before she was able to move in but Pete himself lived there for almost 8 years before his age and declining health forced him into an assisted living home. It must be said that this “dream” house became an emblem for his family, representing his mastery of his profession late into his eighties and early nineties, as well as his spirit in accepting his fate in the wake of the subprime crisis and the shameful failure of the Riverside Bank. Many other people in Fort Pierce suffered as well, but Pete was notable for not becoming embittered by the failure, even though he had lost his entire life savings, and eventually his last house. Anyone who knew Pete would agree that he had an exceptional attitude towards life, hardship and loss notwithstanding. He had a rare gift of making friends, no matter what their origins or social status. He genuinely loved humanity and gave freely of his time and expertise no matter what it cost him in effort or energy. There must be scores of his well-made furniture in houses all over the area, most of them gifts. His workshop on Hartmann Road was always buzzing with activity, with Pete in the middle of his woodworking machines, surrounded by an eternal dust cloud, covered with sawdust and sweat, and smiling all the time. Other favorite activities were collecting orchids, hunting, fishing, camping, and canoeing. He could prepare a 4-course meal over a wood fire in the middle of the wilderness or walk 10 miles across the Florida backcountry in pursuit of a buck, leaving younger men trying to follow and learn, exhausted in his wake. His son Ben remembers one of Pete’s trips to France where Ben and his family lived in a house built in the late 1800s. Pete decided to cover the walls of Ben’s study with bookshelves, built to hug every slope and odd angle. Though Pete did not know French, when Ben took him to the lumber yard and the hardware shop Pete somehow made himself understood down to the smallest nail. The bookshelf is looked on now as an antique masterpiece with a secret closet door that no one has ever been able to spot. Almost every year, while he was still able, he and younger son John would spend a week or two in the wilderness areas of Canada, Minnesota, Wyoming, or Montana, fishing, canoeing, and camping. After his retirement, Olive and Pete continued to entertain at the Delaware house, often with Pete presiding over the barbecue pit. They both were active in community projects, including the creation and expansion of the A.E. Backus Museum. Pete continued building for friends and the community. He built a number of houses and structures for his good friend Bud Adams, all still prized and used on the Adams Ranch. He was a long-time member of the St. Lucie County Historical Society and was a devoted museum guide on Saturday mornings. He built the Pioneer House at Heathcote Botanical Gardens and helped establish the A.E. Backus Scholarship Fund. In 2018, at the age of 99, he was still agile enough to fulfill a life-long dream of seeing Alaska and stepped from a ski plane onto a glacier high up on Mount Denali. His was a life full to the brim with adventure, service, sacrifice, generosity, loyalty, faithfulness, friendship, and kindness. He will be remembered by his family as a loving provider, protector, mentor, and guide. He is survived by his two sons, Ben S. Forkner, with wife Nadine, and John F.D. Peterson, with wife Hope, three grandsons, Benjamin Forkner, Jon Bass, and Mark Bass, two great grandsons, Evan and Owen Bass, and three great granddaughters, Valentina and Natalia Forkner, and Jessica Bass. Plans for a burial service in Fort Pierce will be announced later. In lieu of flowers donations may be made to the A.E. Backus Scholarship Fund.